Adding

a blogospheric comment to a piece by Jon Stone on Fuselit the other day,

I made a point that I want to follow up on here. Jon was responding to WilliamWootten’s stimulating article in the TLS, in which Wootten equated Roddy Lumsden’s editorial imperative in Identity Parade – ‘to spread the word, to educate and

recommend’ – with ‘undifferentiated plurality’, a term that implies an absolute

relativism, unwilling to discriminate on the basis of quality. Wootten is about

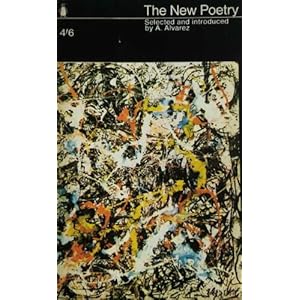

to publish a book on the poets who came to prominence with the publication of

Penguin’s The New Poetry in 1962,

edited by Al Alvarez, and he praises a willingness on the part of Alvarez – and

Ian Hamilton’s Review – to take

strong, contentious positions (for or against) on the poetry they encountered.

Now, I’m all for discrimination. Sadly, the word has become

associated in liberal-minded discourse with its undesirable manifestations, in

matters of race and gender in particular. But the fact that right-thinking

people oppose discrimination on the basis of race and gender is itself an act

of discrimination. Discrimination itself should not be a dirty word: any and every

judgment of value and morality depends upon its activity. As recent neuroscience

has found, the brain itself is essentially an organ of discrimination: an

infinitely complex apparatus through which we might just about negotiate our

presence within the infinitely complicated data of the universe. ‘To be discriminating’

is to exercise a considered and attentive taste. Every poet discriminates (or should do): it’s self-evidently fundamental

to the art. So it is – necessarily – with every poetry editor involved in any

kind of selective process.

I like what excites Wootten about the Sixties

poetry scene, in which the Penguin anthology and Modern Poets series played a galvanizing

part: ‘a moment when contemporary poetry and its values were treated as a

singular artistic arena whose various styles and champions could be debated,

intelligently and passionately if not always in ways capable of clear

resolution’. Are we missing something now, on the Alvarez/Hamilton/Davie/Penguin

Modern Poets model? A more active discourse of articulate discrimination?

I’d certainly like to see more high-level journalism –

let’s say essays, and review essays – devoted to poetry in prominent titles,

yes. And as I commented on the Fuselit piece, there should be room there for

essayists and journalists

to openly champion the work of contemporary writers they appreciate. We have

excellent poetry journals, yes – but with a smaller readership to keep, these

are often under pressure to be representative and inclusive, rather than contentious;

a big readership gives a certain licence, as well as reach.

On the other hand, the debate is now less dependent on the

kind of vehicles Wootten singles out. It’s now a given that the dynamics of the

internet have opened up an ever-growing number of new opportunities to

articulate why and how poetry deserves a reader’s attention. That shouldn’t be

a problem in itself. As ever: it’s content that matters. Wootten’s worry that ‘an

excess of supply – of creative writing courses, career posts, poetry volumes

and prizes and competent but unexceptional poets – rather than a surge in

demand’ lies behind what Lumsden calls the ‘Pluralist Now’, might equally be transposed

and applied to the web. On the whole, I consider the internet a good thing.

Besides, the so-called law of supply and demand is at best a half-truth. In

Aldous Huxley’s wise correction of the familiar phrase: invention is the mother

of necessity.

Likewise,

pluralism is meaningless without discrimination: without difference, there is

no true pluralism. The question is, then, how to accommodate difference – and here,

I invoke the spirit of conversation. Conversation implies a willingness to

listen as well as to speak: to be changed, as well as to change; to be moved,

as well as to move; to learn, as well as to teach. Good conversation is mutual

education: it draws out new orders of insight. Have you noticed how, in the

street or on your doorstep, many religious organisations (it tends to be them,

I’m afraid, or their pseudo-counterparts) try to engage you by asking for a ‘chat’

about this or that? Then you discover that although they want to change you – they

(in my experience) are unwilling to change. That isn’t conversation – it’s

attempted conversion. Chaucer had an eye for these things, and to countervail

the world’s vanities, presented the example of his Clerk of Oxenford:

Sownynge in

moral vertu was his speche,

And gladly wolde

he lerne, and gladly teche.

1 comment:

Just a few footnotes -

Marjorie Perloff writes in Poetry on the Brink: Reinventing the Lyric that "the lack of consensus about the poetry of the postwar decades has led not, as one might have hoped, to a cheerful pluralism animated by noisy critical debate about the nature of lyric, but to the curious closure exemplified by the Dove anthology".

You say - "We have excellent poetry journals, yes – but with a smaller readership to keep, these are often under pressure to be representative and inclusive, rather than contentious". Yes, it can often look that way. I like how The Dark Horse is prepared to champion and re-evaluate. More often one needs to look off-centre for opinions - see for example Andrew Duncan - "The White Stones by J. H. Prynne (1936-) is probably the most significant single volume of the 1960s.", "[Jeremy] Reed is obviously the most gifted poet of his generation", "Wales has not produced any striking books in the 1980s, so far as I have been able to discover, except for the works of Peter Finch", "Larkin had no literary talent ... Larkin never managed to write a good poem", "In 1969 came Children of Albion, Poetry of the Underground in Britain (Penguin, ed. Michael Horovitz); perhaps the worst book I have ever read"

As you say, the WWW means that there are more turfs to war about. If you don't like a game you can take your ball and play elsewhere rather than stand one's ground or engage in debate. Why care about the state of Poetry Review when Jacket 2 (or even a blog) gets more readers?

Post a Comment